Tools of Choice: Making Better Decisions

Photo by Jens Lelie on Unsplash

This article presents some mental models, tips, and pitfalls for decision making.

Introduction

I have been asked how I approach important decisions by some colleagues, and decided to clarify and document the rough mental framework I had been operating with and adding to over the years for making major decisions. This exercise led me to spend quite a bit of time going back over organizational psychology and leadership things I had picked up over the years and researching some new areas as well.

Decision-making related research and knowledge comes from a number of areas. One of those is decision analysis, a sub field of operations research. Another is the research done in psychology, sociology, and economics to analyze cognitive bias. Also risk management and project management best practices have a significant bearing on decision making, since it is often in the context of delivering a project or product.

What is a Decision?

A decision has three components 1) choice, 2) information and 3) preference. (Martin-Vegue, 2021). We will focus here on decisions for work, although most of the material is applicable elsewhere.

The choice includes aspects of the situation that makes a decision necessary or desirable. This may be a problem, an opportunity, or just a desire. Sometimes we have extensive time and resources to make a decision. At other times we have to decide under time-pressure or with limited resources or other constraints.

Preference includes what we want the outcome to be, individually and as part of an organization, such as:

- Greater profit

- Lower risk

- Stronger security

- Stricter policy compliance

- Greater market share

- Earlier date of project delivery

- Higher quality

Information can be qualitative or quantitative with different levels of trust and accuracy associated with it. Frequently it requires time and resources to gather information or actually create it from data analysis. There is nearly always information we would prefer to have that is not available due to cost, time or other constraints.

Types of Decisions

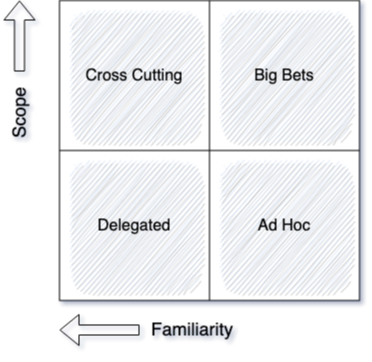

Not all decisions are important or impactful. McKinsey and Co. characterize decisions into four types based on two dimensions, scope and level of familiarity, which is related to frequency (Smet et al,2021).

- Big Bet decisions with major consequences that are infrequent and unfamiliar.

- Cross cutting decisions that are frequent and require broad collaboration across organizational boundaries.

- Ad hoc decisions that are unfamiliar with narrow scope/impact.

- Delegated decisions that can be assigned to a single individual or team

Ad hoc decisions are infrequent and low impact so typically are not a focus for improvement. However, if they are done slowly or bad outcomes are accumulated from them they could have a more significant aggregate impact.

Identify irreversible Decisions. At Amazon, employees try to categorize decisions as either one-way or two-way doors (Anderson, 2021). A one-way door means a consequential decision that cannot be reversed or changed later. If it will permanently affect customer sentiment, or entrench a solution for technical or business relationship reasons then it may be a one-way door. In my experience, there are a lot of decisions which are reversible only with significant effort and expense.

This categorization supports making reversible decisions more efficiently. The less time you spend on reversible decisions the faster you can iterate on a product, feature, or other type of deliverable, and the more time and resources you can spend on the major decisions.

Use Your Internal Compass. Each of us has a different view on what is right in human behavior and what is important in terms of our prioritization of tradeoffs and investments. Being clear on what you value and hold inviolate helps you make better decisions more quickly. More importantly, it helps you make decisions you will be proud of at the end of the day. I think of this as having an internal compass. What choice aligns with what you think is most ethical and important to get right?

In his classic book, The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People,Stephen R. Covey states that “Principles are natural laws that are external to us and that ultimately control the consequences of our actions. Values are internal and subjective and represent that which we feel strongest about in guiding our behavior.” (Covey & Collins, 2020). (view Quote at Goodreads)

I think of principles as things I would make a personal sacrifice to uphold, versus values I would use to evaluate trade-offs. Principles are things you stick to even if it costs you personally, values are things you view as important when making decisions or trade-offs.

"“Knowing yourself is the beginning of all wisdom.”

― Aristotle

Ray Dalio, the founder of the Bridgewater Associates and author of Principles: Life and Work (Dalio, 2020) uses principles to improve his life, work, and decisions. According to Dalio, “Principles are fundamental truths that serve as the foundations for behavior that gets you what you want out of life. They can be applied again and again in similar situations to help you achieve your goals.” In other words, you can use them to streamline decision making.

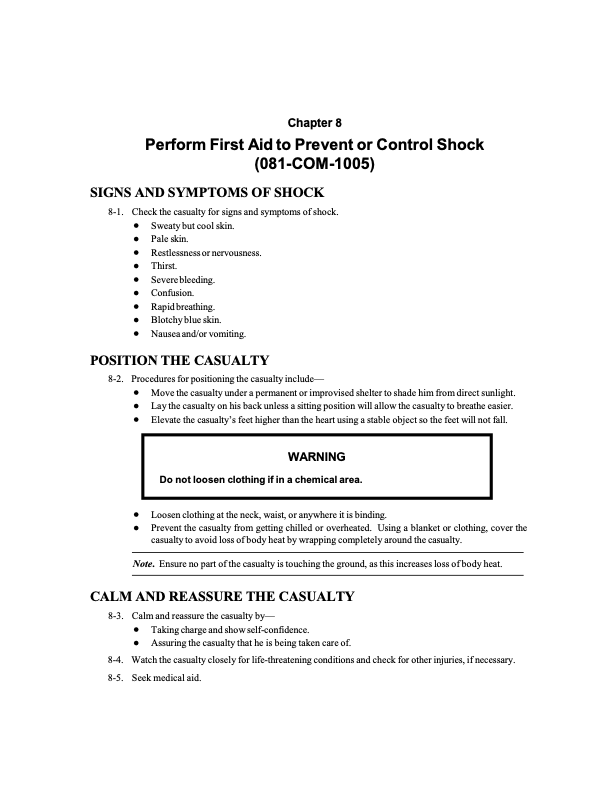

Playbooks and Checklists

If you expect a decision may need to be made quickly under stress due to an incident or emergency then you can create a playbook or checklist for it in advance. See Gawande’s The Checklist Manifesto (2010) for a compelling read on why checklists are worthwhile and why they are relied on in high stakes situations. This is also appropriate if it is an activity you need humans to do repeatedly but isn’t automated (yet) to reduce the chances of human error. Checklists can not replace good judgment, but they are useful to protect against oversights under stress.

This is a checklist to identify, prevent and control shock from the US Army TC 4-02.1 training circular (US Army, 2016).

Decide What Not to Decide

Choose your focus. Spend time on decisions that are both the most important and where you are the most qualified to make the best decision. If they are not your top priority, or you are not the best qualified of those available, consider delegating them or asking for help if you lack the authority to delegate them.

Avoid decision fatigue.This psychological concept is basically the effect of the mental and emotional stress of constantly having to decide things (Berg, 2021). Not every decision is important, and you only have so much time, mental energy, and emotional capacity to invest in making those decisions. Besides causing stress and burnout, decision fatigue also leads to worse decisions.

Manage your habits. Actively examine and control the habits you start, stop, or maintain to reduce the need to make less important, recurring decisions. To establish a new habit, it typically takes a few weeks to a month of willpower and conscious effort. Atomic Habits by James Clear (2018) provides a practical overview of habit management. You can eat the same thing for breakfast, prepare your gym clothes in advance, choose the same day for date night with your spouse, or emulate Steve Jobs and wear an identical outfit everyday. What you spend time on should flow from what you consider important.

Advocacy vs. Inquiry

Be a Detective. Approaching decisions from a viewpoint of curiosity and truth-seeking helps you take an outside view so you can be more objective. According to Matt Gavin in his Harvard Business School blog article, “5 Key Decision-Making Techniques for Managers”, approaching a decision as an inquiry, “[a] mindset that navigates decision-making with collaborative problem-solving” rather than viewing it as a contest(advocacy) improves outcomes by fostering a collaboration (2020). I have experienced this when tasked with finding the right path between different proposals or priorities across different teams. Try to approach the process like a detective rather than having an agenda. This makes it easier to find the best solution holistically when teams or individuals are often, understandably, focused on their individual goals.

Seek Other Viewpoints

There are always limits on the information available and our reasoning abilities. I believe it is critical to have someone review your methodology and conclusions when facing an important decision. Some things to get feedback on include:

- Your assumptions about the situation

- The problem definition’s clarity and relative importance

- The objectivity, accuracy, and relevance of the information and data you used

- Alternatives you considered and any constraints on the options

- Risks or pitfalls you may encounter

- Reasoning supporting your decision

Find someone with a different perspective. Diverse viewpoints lead to better reasoning and decisions. Get feedback from your likely critics, not people likely to agree. Seek to disconfirm your own beliefs to test your assumptions, conclusions, and reasoning. I also try to get feedback on the options before writing down any explicit endorsement of an alternative to avoid biasing others’ thinking.

Include feedback from stakeholders.Getting feedback from stakeholders and incorporating their risks and concerns helps them get onboard with the outcome if it is not the choice they would have made. They are more likely to feel their concerns were heard and considered. This can be important when they will be involved in implementing the decision made.

Decision Making Models

Making decisions can be done in a number of ways in terms of who is involved and what role they play. Besides who is deciding, there are different defined models for reaching a decision. Five basic group decision making methods include:

- Command: the leader decides then informs

- Consultative: the leader gathers input then decides

- Consensus: sometimes with a fallback to another model if not reached

- Democratic: take an actual vote among team or stakeholders

- Delegation: assign to others after setting expectations and then follow-up

Vroom-Yetton

The Vroom-Yetton Decision-Making Model (MindTools Content Team) and its later version the Vroom-Yetton-Jago model (Elmansy, 2015) use a decision tree model for deciding how to decide. This model, sometimes also known as the normative model, uses aspects of the situation to determine the type of decision-making model to use on a spectrum from autocratic through collaborative to fully consensus models. The models the process maps to are similar to the five basic group decision making styles we described above.

Some of the criteria used to choose the decision making model include whether or not the leader has enough time to consult others, how confident the leader is, whether more information is needed from others, how ambiguous the situation is, and whether the team or stakeholders will accept the decision without being involved, and how much the outcome of the decision depends on buy-in from the team. I think this is the most valuable part of this model

WRAP

In their book Decisive (Heath, D., Heath, C., 2013) the Heath brothers present a decision making model with the mnemonic WRAP.

- Widen your options

- Reality test your assumptions

- Attain distance before deciding

- Prepare to be wrong

This model aligns well with my view and sort of maps to a high level meta checklist to keep yourself honest and on track.

Some other specific points from Decisive that I noted as valuable are:

- Overcome biases that distort your decision-making

- Develop options that you hadn’t considered before

- Gather credible information to inform your choices

- Put your emotions into perspective during tough decisions

- Prepare for a decision’s best-case and worst-case scenarios

Use Tenets

Amazon uses tenets for helping to align on how decisions will be made, especially in the case of tie breakers. You can use them to create a framework for the priority of different concerns. According to Danny Sheridan, former Amazonian, “A tenet is a principle or belief that guide[s] decision making.” (2020). You can use tenets to align on important aspects of the decision making process at the start of a team or organization, especially in terms of how to handle competing concerns. For example, is security or reliability more important for your software service? This pre-alignment is usually more calm and considered than making decisions under time pressure.

DARE

Readers familiar with process management terminology will likely know of RACI.. RACI is a model for responsibility assignment and stakeholder management in projects. It stands for Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, and Informed.

DACI is a decision making framework similar to the RACI framework for ownership. DACI stands for Driver, Approver, Contributors, and Informed, and is focused on making efficient decisions as a group. According to the article “DACI Framework: a Tool For Group Decisions” in the PM101 blog, DACI helps “because each team member will have a clear vision of their roles, responsibilities, and expectations.” (Fernandes, 2019).

According to an article published on McKinsey’s People & Organization Blog, DARE is an alternative model to RACI intended to address some pitfalls (Smet, Hewes, & Luo, 2022). The specific concerns with RACI they cite are lack of a clear decider, poor orchestration of stakeholders, poor delegation, and ineffective meetings. DARE tracks decision making roles in four types of involvement: Deciders, Advisors, Recommenders, and Execution stakeholders

Avoid Bias

At this point, there are decades of psychological and sociological research showing a variety of cognitive biases that affect our judgment. A critical part of making good decisions is to be aware of these biases and take measures to counteract their effect on our thinking so we can make more effective and also more fair decisions.

In his book Thinking Fast and Slow,Nobel Laureate David Kahneman (2011) categorizes thinking into two systems which he calls System One and System Two (Kahneman, 2012). Kahneman and his colleague Amos Tversky did much of the early work around different types of cognitive bias such as availability bias which they referred to as the availability heuristic (Tversky, Kahneman, 1973).

The system one mode is intuitive and uses heuristics to make intuitive decisions quickly. Heuristics are basically mental shortcuts, in this case subconscious ones. This is how you can catch a ball once you have learned by estimating its future location successfully, but it is also why people have poor intuition for probability and statistics.

System two is the system used when you are consciously taking your time to think about something such as how to apply the quadratic formula to an equation or to interpret the rules for tax incentives. When you need to be creative and produce more options, your intuitive thinking, especially free association with a diffuse focus, can help you think more broadly about a challenge or situation.

In situations where you have taken in a lot of new information and want to avoid subjectivity or bias, then leaving the decision for later by sleeping on it or focusing on other work for a period of time can help you integrate what you have learned into your memory, since sleep is an important factor in forming long-term memory. Time away from the issue also helps you see it from a different perspective because our state of mind affects our bias, for example if we are upset, tired, or hungry we will be more pessimistic.

When math, statistics, or other numeric concerns are involved, system two is your friend. There are numerous studies showing just how poorly human intuition functions for probability, relative scale, and statistics. For example, people fall prey to the law of small numbers frequently, even when they have the technical knowledge of statistics to know better (Tversky & Kahneman, 1971).

Common Biases

Some cognitive biases pertinent to decision making include:

- Confirmation bias: the tendency to weight data agreeing with your current viewpoint more heavily than data which contradicts it.

- Availability bias: the tendency to overweight more mentally available data, such as recent data (recency bias), or examples you are more familiar with than others.

- Anchoring: the tendency to bias towards numeric values which framed (closely preceded) a decision, even those which are completely unrelated.

- Survivorship: this is a type of selection bias, where the examples available are not representative of the population. An excellent historical example is the analysisof Abraham Wald regarding which areas of aircraft to reinforce against bullets in WWII.

- Self serving bias:attributing positive outcomes to our character or actions, but blaming negative results to external factors or others (Decision Lab).

- Framing effect: people’s tendency to select different options is affected by whether they are framed positively or negatively (Tversky & Kahneman, 1981)

- Recency bias: giving too much weight to recent examples or data, see Availability Bias

- Planning fallacy: bias towards optimism during planning when estimating costs and benefits instead of realistic view of the probability of gain and loss. (Kahneman & Tversky, 1982).

- Fundamental Attribution Error: overemphasize dispositional (personality) factors and underemphasize situational ones. (The Decision Lab).

- Illusion of control: underestimating uncertainty due to belief that we have more control over events than we actually do

A more comprehensive list of cognitive biases is covered in the Wikipedia article, List of Cognitive Biases (2023, September 29).

Reference Class Forecasting

Decisions are often made based on estimates of how much work and time it will take to complete an option. This makes bias affecting estimation costly.

The planning fallacy is pernicious. In my experience it often contributes to rewriting systems that could have been equivalently improved for less cost and “not-invented-here” syndrome where engineers and leaders believe they can develop their own system instead of using an existing one. In order to avoid the planning fallacy, we should try to take the outside view, and to check our assumptions. The most useful tip I know for this particular problem is to rely on reference class forecasting whenever possible. The cost, complexity, and duration of a project should be based on the observed values from the most similar projects for which you have available data.

The article Delusions of Success: How Optimism Undermines Executives’ Decisions provides a good overview of the planning fallacy with examples, (Lovallo & Kahneman, 2003).

Prepare to Face Reality

“No plan of operations reaches with any certainty beyond the first encounter with the enemy’s main force.”

– Helmuth von Moltke 1800–91, Prussian military commander in the Kriegsgechichtliche Einzelschriften (1880).

Often quoted as:

“No plan survives first contact with the enemy” Sourced from Oxford Essential Quotations (4 ed.). See also“Helmuth von Moltke the Elder” at Wikipedia.

Perform a Premortem

Preparing for failures can actually increase the odds of success. In his TEDx talk, Before You Decide: 3 Steps To Better Decision Making, Matthew Confer lays out three steps to improve decision making (2019), beginning with “Embrace a pre-mortem” to work backwards from an assumption of future failure to identify potential issues and brainstorm how to prevent them. A premortem “operates on the assumption that the patient has died, and so asks what did go wrong. The team members’ task is to generate plausible reasons for the project’s failure.” (Klein, 2007). People can be hesitant to voice concerns; this process relieves some of the social friction that interferes with an open discussion of risks.

Risk Assessment

Analyzing the risks associated with a decision helps produce better decisions and improve the chances of achieving a desirable outcome during implementation. A practical risk management approach by Becker (2004) covers the risk management process recommended by the Project Management Institute.

The steps in a typical risk management process are:

- Identify the risks. This is where the premortem is helpful.

- Assess the risks. Estimate the likelihood of occurrence and severity if it does.

- Identify possible mitigations to reduce the likelihood or severity of risks.

- Prioritize which mitigations to put in place.

- Monitor the implementation.

Summary

It is much simpler to learn the type of biases that exist than it is to avoid being affected by them. This is why feedback, structure, and curiosity are important. Testing our reasoning against diverse views helps us see past unconscious bias and narrow framing. I recommend reading more about cognitive bias at The Decision Lab (2011), Wikipedia, and in the classic bookThinking, fast and slow (2011) or this article in Scientific American (2012) both by Daniel Kahneman.

The key takeaways for this article are:

- Focus on what’s important.

- Prefer inquiry over advocacy.

- Seek out feedback.

- Add structure by using a model.

- Beware of bias.

- Manage risks proactively

I hope you have found this article useful. Please reach out if you have feedback or related tips you think would help others.

References

Anderson, D. (2021, October 21). Two-way doors are great and one-way doors are scary - thoughtful decision-making. Scarlet Ink by Dave Anderson - Leadership Advice. Retrieved February 23, 2023, from https://www.scarletink.com/two-way-doors-vs-one-way-doors/

Becker, G. M. (2004). A practical risk management approach. Paper presented at PMI® Global Congress 2004—North America, Anaheim, CA. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

Confer, Matthew. (2019, May). Before You Decide: 3 Steps To Better Decision Making. TEDxOakLawn, TED Conferences. https://www.ted.com/talks/matthewconferbeforeyoudecide3stepstobetterdecisionmaking

Covey, S. R., & Collins, J. C. (2020). The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Powerful Lessons in Personal Change. Simon & Schuster.

Dalio, R. (2020). Principles life and work. MTM.

Decision Lab, The. (n.d.). The Fundamental Attribution Error, explained. Retrieved Oct 3, 2023 from https://thedecisionlab.com/biases/fundamental-attribution-error

Decision Lab, The. (n.d.). Why do we blame external factors for our own mistakes? Retrieved Oct 9, 2023 from https://thedecisionlab.com/biases/self-serving-bias.

Elmansy, R. (2015). Vroom-Yetton-Jago: Deciding How to Decide. Retrieved from https://www.designorate.com/vroom-yetton-jagohow-to-decide/ Sep 30, 2023.

Fernandes, Thaisa. (2019). “DACI Framework: A Tool For Group Decisions”. PM101 blog. Retrieved Oct 9, 2023 from https://medium.com/pm101/daci-framework-a-tool-for-group-decisions-665bd71585cf.

Gavin, Mark. (2020, Mar 31). “5 Key Decision-Making Techniques for Managers”. Harvard Business School Online’s Business Insights Blog. Retrieved Oct 4, 2023 from https://online.hbs.edu/blog/post/decision-making-techniques.

Gawande, A. (2010). The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right. United States: Henry Holt and Company.

Heath, D., Heath, C. (2013). Decisive: How to Make Better Choices in Life and Work. United States: Crown.

Jones, S. (2021, Aug 11). Hedge-fund billionaire Ray Dalio lays out 4 steps to making better decisions - and says think like Picasso. Business Insider. Retrieved February 23, 2023, from https://www.businessinsider.com/ray-dalio-principles-careers-and-decision-making-picasso-2021-8

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1982). Intuitive prediction: Biases and corrective procedures. In D. Kahneman, P. Slovic, & A. Tversky (Eds.), Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases (pp. 414-421). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511809477.031

Kahneman, Daniel (2011).Thinking, fast and slow. London: Penguin Books. pp. 14.ISBN 9780141033570.

Kahneman, D. (2012, June 15). Of 2 minds: How fast and slow thinking shape perception and choice [excerpt]. Scientific American. Retrieved Sep 21, 2023 from https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/kahneman-excerpt-thinking-fast-and-slow/

Klein, G. (2007, Sep.). Performing a Project Premortem. Harvard Business Review.

Lovallo, D. & Kahneman, D. (2003, July) Delusions of Success: How Optimism Undermines Executives’ Decisions. Harvard Business Review.

Martin-Vegue, Tony. (2021, April 12). _Using Risk Assessment to Support Decision Making. _Information Systems Audit and Control Association. Retrieved Oct 3, 2023 from https://www.isaca.org/resources/news-and-trends/industry-news/2021/using-risk-assessment-to-support-decision-making.

MindTools Content Team, (n.d.). _The Vroom-Yetton Decision Model. _Retrieved Sep 30, 2023 from https://www.mindtools.com/adamhmy/the-vroom-yetton-decision-model

Sheridan, Danny. (2020). Tenets at Amazon: Fact of the Day 1. Published in Fact of the Day 1. Retrieved Oct 2 from https://medium.com/fact-of-the-day-1/tenets-at-amazon-a2bb8a56ae94

Smet, A. D., Lackey, G., & Weiss, L. M. (2021, March 1). Untangling your organization’s decision making. McKinsey & Company. Retrieved February 23, 2023, from https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/people-and-organizational-performance/our-insights/untangling-your-organizations-decision-making

Smet, Aaron De, Hewes, Caitlin, & Luo, Mengwei. (2022, July 25). The limits of RACI—and a better way to make decisions. People & Organization Blog. Retrieved Oct 5, 2023 from https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/people-and-organizational-performance/our-insights/the-organization-blog/the-limits-of-raci-and-a-better-way-to-make-decisions

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1971). Belief in the law of small numbers. Psychological Bulletin, 76, 105-110.

Tversky, A, Kahneman, D. (1973). Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability, Cognitive Psychology, Volume 5, Issue 2, Pages 207-232, ISSN 0010-0285, https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0285(73)90033-9.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1981). The Framing of Decisions and the Psychology of Choice. Science, 211(4481), 453–458. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1685855

U.S. Army. (2016). TC 4-02.1 Training Circular. Retrieved Oct 11, from https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DRpubs/DRa/ARN14135-TC_4-02.1-002-WEB-3.pdf.

Wikipedia contributors. (2023, September 29). List of cognitive biases. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 02:51, October 3, 2023, from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Listofcognitive_biases&oldid=1177703363