90 Minutes from Concept to Code: Building LowPolyCartJS with AI Agents

Introduction

Between 6:30 AM and 7:53 AM one morning, I built a functional 3D racing prototype from scratch. LowPolyCartJS went from a blank terminal to a modular Three.js engine, complete with procedural world generation, physics, and a custom UI. The timeline is less important than the workflow: this was an experiment in spec-driven development using three distinct AI layers—generative art, architectural planning, and agentic coding.

This article explores what worked, what didn’t, and what I learned about combining generative tools with clear technical specifications. The project is available on GitHub and playable on itch.io.

Why This Approach?

The motivation came from a practical question: can we move beyond “vibe coding” to something more systematic? When working with AI coding assistants, the quality of output depends heavily on the quality of input. Vague prompts produce vague code. Detailed specifications produce more reliable implementations.

This project tested whether a structured workflow—specification first, then implementation—could yield better results than iterative prompt engineering. The answer, as we’ll see, is nuanced.

The Three-Layer Workflow

The workflow consisted of three distinct phases, each using different AI tools for different purposes:

- Art Layer: Generative 3D assets using Meshy.ai

- Architectural Layer: System design and specification using Gemini

- Implementation Layer: Code generation using Claude Code

Each layer had different requirements and constraints, which shaped how I used the tools.

Layer 1: Generative Assets with Meshy.ai

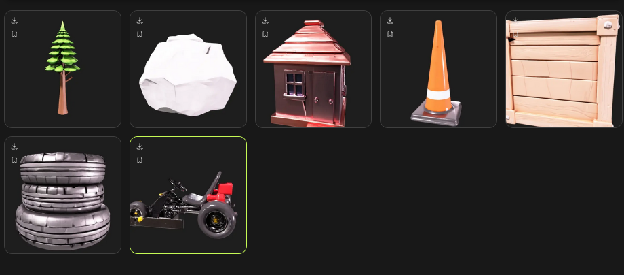

The biggest bottleneck in 3D development is asset creation. For this project, I used Meshy.ai to generate a “kit of parts"—a kart, trees, and rocks—rather than modeling them manually or sourcing from asset stores.

The Art Bible Pattern

The key insight wasn’t just writing good prompts, but maintaining consistency across all asset generation. I created what I call an Art Bible: a consistent suffix appended to every prompt that ensures visual coherence.

Every Meshy.ai prompt ended with: "stylized low-poly game asset, chunky geometric shapes, vibrant solid colors, clean topology"

This ensured that regardless of what object I was generating, they all shared the same visual DNA. The kart, trees, and rocks felt like they belonged in the same world, even though they were generated separately.

The Normalization Problem

Generative 3D models often come with inconsistent scales and pivot points. A tree might be 10 meters tall in one generation and 2 meters in the next. Pivot points might be at the bottom, center, or top of the model.

Rather than manually fixing each model in Blender or another 3D editor, I solved this programmatically by building a normalization pipeline in the code itself. The AssetLoader calculates bounding boxes using THREE.Box3, then scales and translates models to consistent dimensions and pivot points.

This approach has trade-offs. It’s faster than manual editing, but it means the normalization logic lives in code rather than in the assets themselves. For a prototype, this was acceptable. For production, you’d want to bake these transformations into the models.

Layer 2: Spec-Driven Architecture

Before writing or generating any code, I spent the first 15 minutes defining a Master Specification. This wasn’t a formal document—it was a structured conversation with Gemini where I broke the engine into six “Mini-Milestones":

- Asset Normalization: Auto-scaling models based on bounding boxes

- Physics: A velocity-based “Tank Drive” system (no realistic car physics)

- World Management: Procedural scattering with JSON serialization

- State Machine: Managing transitions from “3-2-1-GO” to “Racing”

- UI & Feedback: CSS speedometers and positional audio

- Camera System: Smooth chase camera with FOV stretching at high speeds

The Specification Process

I created this specification by pasting all responses from my Gemini session into a Google Doc, then exporting the entire document to Markdown at the end. The resulting specification is available in the repository: Cart Minimal Reference Engine.md.

You can see this has had basically zero editing to tune the output, but I did ask Gemini to review the document as one of the final phases and provide feedback, which you can see in the section “Feedback on Final Polish of this Document”.

The specification served multiple purposes:

- Clarity: It forced me to think through the architecture before implementation

- Context: It provided Claude Code with a detailed roadmap, reducing hallucinations

- Modularity: Breaking the system into milestones made it easier to implement incrementally

What Worked, What Didn’t

The specification was effective at preventing architectural drift. When Claude Code generated code, it had clear constraints and goals. However, the specification wasn’t perfect. Some details were ambiguous, and I had to clarify requirements during implementation.

The key lesson: specifications don’t need to be perfect, but they do need to be sufficient. A good specification provides enough detail to guide implementation without being so rigid that it prevents necessary adjustments.

Layer 3: Implementation with Claude Code

With the specification finalized, I used Claude Code to implement it. The agent generated three main files: loader.js, world.js, and main.js. Because the agent had a modular roadmap from the specification, it was able to generate code without significant hallucinations or architectural drift.

Three.js Implementation Details

The agent handled several non-trivial Three.js tasks:

The Loader: Calculating THREE.Box3 bounding boxes to normalize a 2,000-poly Meshy kart to exactly 1.5 meters tall, regardless of how it was exported.

The Camera: Implementing a .lerp smoothed chase camera that dynamically stretches its Field of View (FOV) at high speeds to simulate motion. This creates a sense of speed without requiring complex motion blur or post-processing.

Positional Audio: Mapping engine pitch to velocity so the car “revs” as you accelerate. The audio system uses Web Audio API with 3D positioning relative to the camera.

The GLB Pipeline Challenge

For developers looking to replicate this, the core challenge is the GLB Pipeline. In LowPolyCartJS, the AssetLoader is the heart of the project. It doesn’t just load a file; it:

- Traverses the scene graph to enable shadows on all meshes

- Sets the model’s bottom to Y=0 (normalizing pivot points)

- Scales models to consistent dimensions

- Handles materials and textures

This ensures that when the WorldManager scatters objects procedurally, they are perfectly grounded on the grid, regardless of how they were exported from Meshy.ai or other AI tools.

The GLB format (binary glTF) is well-supported in Three.js, but working with procedurally generated models requires careful handling of scene graphs, materials, and transformations.

What I Learned

Spec-Driven Development Works, But…

The specification-first approach was effective. It provided structure and prevented the kind of drift that happens when you iterate on prompts without clear goals. However, it’s not a silver bullet:

- Specifications take time: The 15 minutes spent on specification saved time during implementation, but it’s still an upfront cost

- Specifications need iteration: Some details only become clear during implementation

- AI tools vary: What works for architectural planning (Gemini) might not work for code generation (Claude Code)

The Role of the Developer Is Shifting

This project reinforced something I’ve observed in other AI-assisted development work: we’re moving from writing code to specifying and orchestrating. The developer’s role becomes:

- Architect: Define the system structure and constraints

- Orchestrator: Coordinate multiple AI tools and workflows

- Reviewer: Validate and refine AI-generated output

- Integrator: Connect the pieces and handle edge cases

This doesn’t mean developers become obsolete—it means the skills that matter are shifting toward specification, review, and integration.

Combining Tools Requires Careful Orchestration

Each AI tool has strengths and weaknesses:

- Meshy.ai: Great for generating 3D assets quickly, but requires consistency patterns (Art Bible) to maintain visual coherence

- Gemini: Effective for architectural planning and specification, but needs structured input to produce useful output

- Claude Code: Strong at code generation when given clear specifications, but can drift without constraints

The workflow succeeded because each tool was used for what it’s good at, and the outputs were integrated carefully rather than chained automatically.

The Workflow Summary

For developers interested in replicating this approach, the workflow is:

- Define the Spec and Art Bible: Spend time upfront on architecture and visual consistency

- Generate assets: Use generative tools with consistent prompts

- Implement iteratively: Use AI coding assistants with clear specifications

- Review and refine: Validate output, fix edge cases, integrate pieces

The timeline—90 minutes—is less important than the structure. A similar workflow could take longer or shorter depending on complexity, but the principles remain the same.

Distribution and Next Steps

After the initial 90-minute build, I set up Vite to build the project for distribution (not included in the timeline). This enabled easy sharing and publishing to itch.io.

The project demonstrates that combining clear technical specifications with powerful generative tools can significantly shorten the distance between an idea and a shipped repository. However, it also shows that this requires careful orchestration and review—the AI tools amplify your ability to build, but they don’t replace the need for clear thinking and systematic workflows.

Explore the project: github.com/ranton256/LowPolyCartJS

Play or download: itch.io