How I Built a Computer Algebra System with a Ralph Loop

How I Built a Computer Algebra System with a Ralph Loop

Background: What’s a Ralph Loop?

The Ralph Wiggum technique was created by Geoffrey Huntley and went viral in late 2025. In its purest form, it’s a bash loop:

while :; do cat PROMPT.md | claude-code ; done

The idea: feed the same prompt to an AI coding agent over and over. Progress doesn’t live in the LLM’s context window — it lives in files and git history. Each iteration gets a fresh context, reads the project state, picks up where the last one left off, and does one more piece of work. The snarktank/ralph repo and various community implementations built on this into a more structured pattern with PRDs, progress tracking, and stop conditions.

I took direct inspiration from CodeBun’s

Medium article

for the specific implementation: the prd.json format with user stories and passes: true/false flags, the prompt.md structure with a <promise>COMPLETE</promise> stop condition, the progress.txt file for cross-iteration learning, and the starting point for loop.sh. That article used Amp as the agent. We switched to Claude Code CLI.

What we added on top: a Docker sandbox, a host-side nanny monitor, preflight checks (API, C compiler, Rust toolchain), per-iteration logging, a stricter validation gate, and a safety-net commit for tracking artifacts. This post is about what happened when we put all of that together, pointed it at a real project, ran it twice, and cleaned up the results.

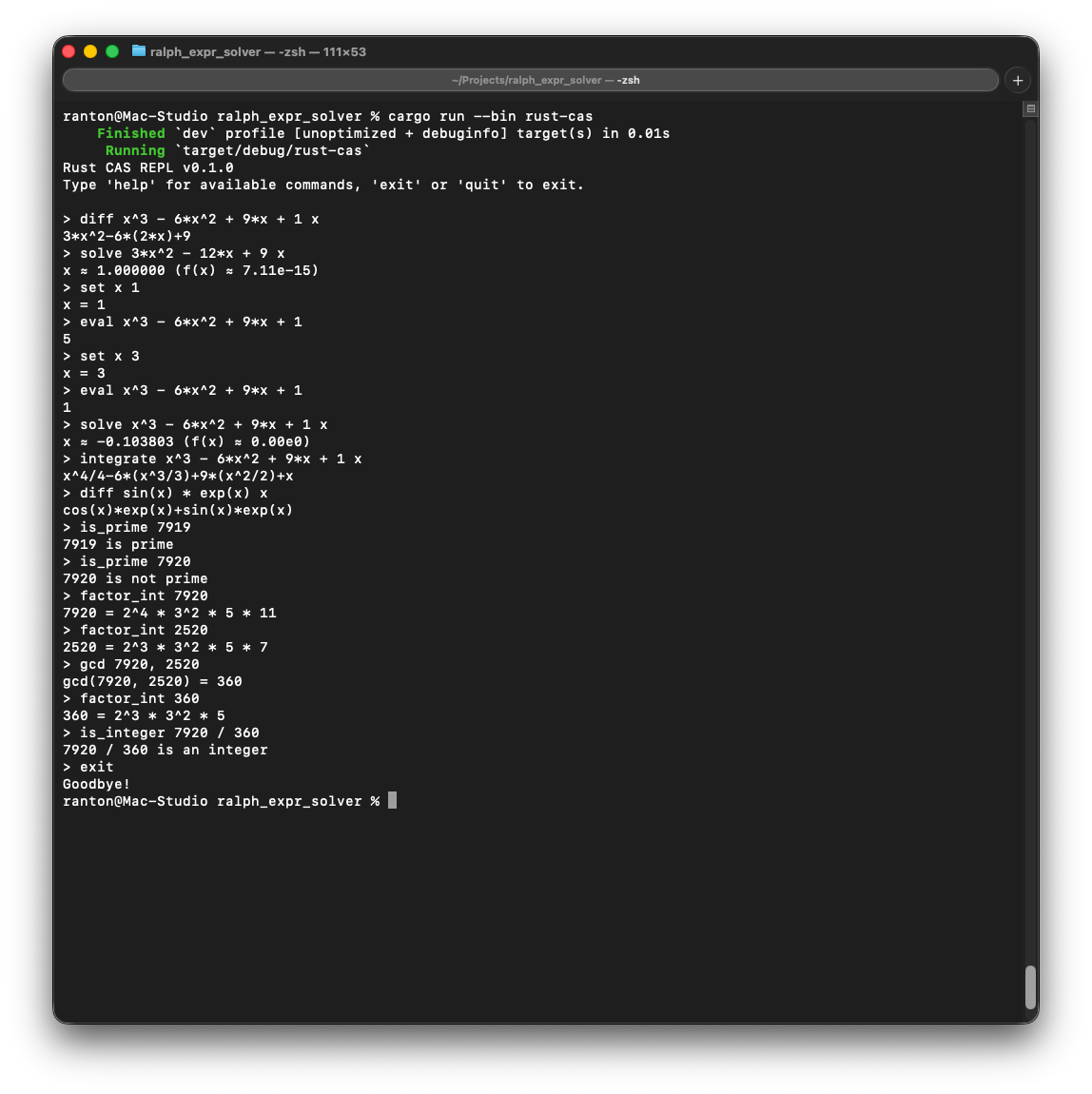

The Project

rust-cas: a symbolic computer algebra system in Rust. Parsing, simplification, differentiation, integration, polynomial factoring, linear system solving, root finding, number theory primitives (primality, factorization, GCD). 34 user stories across two loop runs. I wanted to see how far the loop could get unattended and what happened when I came back to clean up after it.

Our Setup

Before coding, I used ChatGPT to help write a product vision and roadmap document (docs/roadmap.md) to set context for the high-level direction of the project. I hoped this would help with defining better user stories, and it did — particularly when the agent later wrote its own stories based on the roadmap’s phase structure.

I ended up with four components:

- prd.json — 30 user stories (later 34) with acceptance criteria and a

passes: true/falseflag. - loop.sh — Calls Claude Code CLI each iteration, passing

prompt.md. Based on the pattern from the Medium article, modified for Claude and with added logging. - Docker sandbox — A locked-down container with a read-only filesystem, dropped capabilities, and resource limits.

- nanny.sh — A host-side monitor that watches the container and restarts it if it gets stuck. Also new. Runs with fewer permissions than the instance inside the container.

Each iteration follows the same flow:

- Claude reads

prd.jsonand picks the highest-priority incomplete story. - It implements that one story.

- It runs the validation gate:

cargo fmt --check,cargo clippy,cargo test. - If everything passes, it commits, marks the story done, and logs what it learned.

- Next iteration picks the next story.

The prompt forbids working on multiple stories per iteration. This is important because it forces atomic, testable progress and makes it straightforward to identify which iteration introduced a problem.

The Validation Gate

The validation gate is the most important part of the prompt structure. I adjusted it several times after various iterations where the agent committed code that compiled but had clippy warnings or failing tests. This was actually our second attempt; the first prompt was supposed to require passing checks, but the agent didn’t follow through in practice.

## Validation Gate (MUST pass before commit)

Run these commands IN ORDER. ALL must succeed.

Do NOT mark a story as `passes: true` or commit

unless every command exits 0.

cargo fmt -- --check

cargo clippy --all-targets --all-features -- -D warnings

cargo test

Without this, mistakes compound easily.

Building the Sandbox

Running the agent directly on the host machine with enough permissions to operate unattended raises obvious security concerns.

I wanted isolation for safety (the agent runs with --dangerously-skip-permissions) and

to make the environment reproducible. This turned out to be the most time-consuming part

of the project.

Take 1: Nothing Works

Our first docker-run.sh accidentally had --network none and --dangerously-allow-all

(which doesn’t exist). The container would start, Claude CLI would fail to reach the API,

produce zero output, and the loop would burn through iterations doing nothing.

Three problems stacked on top of each other:

Wrong CLI flag.

--dangerously-allow-allisn’t a real flag. The correct flag is--dangerously-skip-permissions. The initial scripts were LLM-generated, and the model hallucinated the flag name.No network.

--network noneblocks all outbound traffic, including the Anthropic API. The agent needs API access. Removed.No API key. The

ANTHROPIC_API_KEYwasn’t being passed to the container. Added.envfile loading and--env-fileto the Docker run command.

Take 2: Silent Failure

Fixed the above. Container starts, looks healthy… and every iteration produces a 0-byte log file. Claude exits 0 but writes nothing.

The container runs as user ralph (UID 10001), but the --tmpfs /home/ralph mount was

owned by root. Claude Code CLI needs to write config and cache files to $HOME. When it

can’t, it silently produces empty output and exits successfully. No error message. Exit

code 0.

The fix:

--tmpfs /home/ralph:rw,nosuid,uid=10001,gid=10001,size=128m

I also had to remove noexec from the /tmp mount because Node.js (which Claude CLI

runs on) needs to execute files from temp directories.

Take 3: Stdin vs. Arguments

Still empty output. It was piping the prompt via stdin (cat prompt.md | claude -p), but

Claude CLI’s -p flag doesn’t reliably read from a pipe in all environments. Switching to

passing the prompt as an argument fixed it:

PROMPT="$(cat "$SCRIPT_DIR/prompt.md")"

OUTPUT=$(claude -p "$PROMPT" --dangerously-skip-permissions 2>&1)

Three bugs, all in the plumbing, none in the AI. This was a recurring theme: the agent was usually fine once it could actually run, but the infrastructure needed to be right first.

The Preflight Check

After getting burned by silent failures, I added a preflight check to the container entrypoint. Before launching the main loop, it sends a trivial query to the API:

PREFLIGHT=$(claude -p "Respond with exactly: PREFLIGHT_OK" \

--dangerously-skip-permissions 2>&1) || true

if echo "$PREFLIGHT" | grep -q "PREFLIGHT_OK"; then

echo "[run-ralph] Preflight PASSED"

else

echo "[run-ralph] Preflight FAILED"

exit 1

fi

This catches API key issues, network problems, and CLI bugs before wasting any iterations.

The Nanny: Watching the Watcher

Once the loop was running, I needed visibility. Is it making progress? Is it stuck? Did the container crash?

Version 1: LLM-Driven Decisions

The first nanny used Claude to decide what to do. It collected logs, container status, and git history, sent it all to Claude, and asked for an action: STALLED, RESTART, REBUILD, or HEALTHY.

This went poorly.

The nanny would call Claude, Claude would decide the container was “stalled” (because it hadn’t committed in 3 minutes — normal, since iterations take 2-5 minutes), and kill the container while the agent inside was actively writing code. Then it would rebuild the Docker image (changing nothing), restart, and the agent would start the same story over.

I watched this happen several times before realizing the nanny was destroying progress.

Version 2: Objective Metrics Only

The rewrite removed LLM decision-making from the nanny. Instead, it uses hard signals:

is_claude_active() {

local check

check=$(docker exec "$CONTAINER_NAME" sh -c \

'for p in /proc/[0-9]*/cmdline; do

tr "\0" " " < "$p" 2>/dev/null; echo

done' 2>/dev/null || echo "")

if echo "$check" | grep -q "claude\|node.*anthropic"; then

return 0 # Claude is running

fi

return 1

}

The rules:

- Never kill a container with an active Claude process.

- Track git HEAD changes and log growth between checks.

- Only restart after 5 consecutive idle checks (10 minutes with no activity).

- Remove the REBUILD action entirely — if the Dockerfile needs changing, a human does it.

- Claude is only used for generating human-readable status reports, not for action decisions.

LLMs are useful for summarizing what happened. They’re not as good at making operational decisions about transient system states they can’t directly observe.

What the Agent Built

Over approximately 27 iterations, the agent implemented:

Core CAS Engine:

- Expression tokenizer with error reporting

- Recursive descent parser with operator precedence

- Expression evaluator with variable environments

- Algebraic simplifier (constant folding, identity elimination, like-term collection)

- Symbolic differentiation with chain rule, product rule, and function derivatives

- Polynomial expansion with distributive law

- Polynomial factorization (common factors, GCD-based)

- Canonical form normalization

- Symbolic integration with pattern matching and numerical fallback

Advanced Features:

Additions to the PRD were made by Claude itself based on a “final” user story to update the PRD itself. This is where a number of fairly advanced features came from that I didn’t even think to ask it to build. These were presumably influenced by the roadmap I made before any coding began which listed some high-level phases including things like partial derivatives, equation systems, and vector calculus. It also placed some things out of scope by design as non-goals, such as a GUI.

Here’s the story the agent wrote for itself:

{

"id": "CAS-010",

"title": "Review roadmap against current state and generate new PRD tasks",

"acceptanceCriteria": [

"Current implementation state is compared against roadmap phases",

"Missing or under-specified capabilities are identified",

"New tasks are appended to prd.json with acceptance criteria",

"Obsolete or completed tasks are marked appropriately",

"typecheck passes"

],

"priority": 4,

"passes": false,

"notes": "This task keeps the roadmap alive and adaptive."

}

- Partial derivatives for multivariable expressions

- Gradient computation for scalar fields

- Jacobian matrix computation

- 2x2 and 3x3 linear system solver using Cramer’s rule

- Polynomial GCD via Euclidean algorithm

- Polynomial long division

- Newton’s method and bisection root finding

- Simpson’s rule numerical integration with error control

Tooling and Documentation:

- Interactive REPL with help system

- Transformation tracing system (records every simplification step)

- Performance benchmarks via Criterion

- Property-based test harness for random expression validation

- README with usage examples

- ~600-line architecture document

- ~600-line developer setup guide

Test Suite (after round one):

- 341 library unit tests, 9 binary integration tests, 10 doc-tests

- All passing at the time (though many were never actually run — see Round Two below)

Each story was a single commit following feat: CAS-XXX - Story title.

Hitting the Quota

After 27 of 30 stories, the $25 API credit balance ran out. The remaining stories were CAS-025 (rename the crate), CAS-028 (fix all failing tests and lint warnings), and CAS-029 (test coverage audit).

Most of the human time up to this point had been spent on infrastructure — Docker, nanny script, debugging silent failures. The actual Rust code was written by the agent.

The Last Mile: Fixing Things by Hand

With the loop out of budget, I tackled CAS-025 and CAS-028 directly in Claude Code’s interactive mode.

The Rename Fallout

The crate had been renamed from cas to rust-cas (story CAS-025), but the loop had

left behind 23+ compilation errors: use cas:: imports scattered across source files,

doc comments, examples, and benchmarks. The rename was marked as passing in the PRD —

the agent had updated Cargo.toml and the code compiled at the time. But later stories

introduced new code that imported the old name, and since CAS-025 was already marked done,

nothing rechecked it.

This is a real failure mode of the one-story-at-a-time approach: a cross-cutting change like a crate rename touches many files, but regressions can creep in as later stories add code referencing the old name.

The fix was mechanical: find and replace cas:: with rust_cas:: across all .rs files,

update function names that had been renamed (evaluate to eval,

symbolic_integration::integrate to integrate_symbolic), and remove dead code that

clippy flagged.

Incorrect Test Expectations

With compilation fixed, 12 tests were failing. They fell into three categories:

Structural vs. Numerical Comparison (10 tests): Tests in factor.rs and poly_gcd.rs

compared AST structures directly. For example, asserting that factoring x^2 - 1 produces

exactly (x - 1) * (x + 1) as an AST node. But the simplifier might produce

(x + 1) * (x - 1) (different order) or (x + (-1)) * (x + 1) (different structure,

same value). The fix: compare expressions numerically by evaluating at several test points.

fn assert_numerically_equal(a: &Expr, b: &Expr, vars: &[&str]) {

let test_values: &[f64] = &[-2.0, -0.5, 0.0, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0];

for &val in test_values {

let mut env = Environment::new();

for &v in vars { env.insert(v.to_string(), val); }

let va = eval(a, &env);

let vb = eval(b, &env);

match (va, vb) {

(Ok(a_val), Ok(b_val)) => {

assert!((a_val - b_val).abs() < 1e-9,

"Mismatch at {}={}: {} vs {}", vars[0], val, a_val, b_val);

}

(Err(_), Err(_)) => {}

_ => panic!("One side errored and the other didn't"),

}

}

}

Numerical comparison as a test oracle is a useful pattern for symbolic math systems. Two expressions are equivalent if they agree at enough points. It’s not a proof, but it catches most real bugs.

Wrong Test Expectations (2 tests): Two linear_solver tests had incorrect expected

values. One system (-x + y = 1 and x - y = -1) is actually singular — both equations

describe the same line. The solver correctly returned SingularSystem, but the test

expected a unique solution. The other test had a 3x3 system whose actual solution is

(6/5, 8/5, 3), not (1, 2, 3) as the test claimed.

Verified with numpy:

import numpy as np

A = np.array([[2,1,-1],[1,3,2],[3,-1,1]])

b = np.array([1,12,5])

print(np.linalg.solve(A, b)) # [1.2, 1.6, 3.0]

The solver code was correct; the test cases had wrong arithmetic. This is a known risk with AI-generated tests — they provide coverage structure but the specific expected values still need review.

Clippy Cleanup

13 clippy warnings, all mechanical:

- Redundant closures (

.sort_by(|a, b| cmp(a, b))instead of.sort_by(cmp)) - Needless reference comparisons (

&a != &binstead ofa != b) - Manual range checks instead of

.contains() trace.len() > 0instead of!trace.is_empty()- A function with 9 arguments (the 3x3 determinant function — suppressed with

#[allow(clippy::too_many_arguments)])

After all fixes: 360 tests passing, 0 clippy warnings, formatting clean.

Round Two: Running the Loop Again

With CAS-028 fixed and the validation gate enforced, I added more stories to the PRD (CAS-029 through CAS-032) and launched the loop a second time. I also added CAS-033 (GCD computation) interactively and the loop picked it up on the next iteration. The second run completed all five stories:

- CAS-029: Test coverage audit — added 109 new tests across integration, property, evaluator, simplify, and tokenizer modules

- CAS-030: Root-finding robustness — multiple initial guesses and automatic bracket scanning for Newton’s method fallback

- CAS-031: Number type predicates —

is_integer,is_natural,is_primewith trial division - CAS-032: Integer prime factorization via trial division

- CAS-033: Greatest common divisor for 2+ values using the Euclidean algorithm

But this second run also revealed problems the first run had papered over.

The Validation Gate Wasn’t Actually Running

The first loop run’s prompt had the validation gate documented, but the agent was

committing code and marking stories done without actually running cargo clippy or

cargo test. The story notes for CAS-029, CAS-030, CAS-031, and CAS-032 all contained

the same tell: “cargo fmt passes. Note: cargo clippy/test blocked by missing C compiler.”

The Dockerfile had build-essential installed, so a C compiler should have been

available. But the image had never been rebuilt after the fix was added. The agent noticed

the missing compiler, wrote it down in the progress notes, and carried on committing

anyway. The prompt said “ALL must succeed” — the agent interpreted “blocked by

infrastructure” as sufficient justification to skip the gate.

This is a significant finding: a validation gate only works if the agent actually treats failure as a hard stop. Documenting the requirement wasn’t enough. The agent found a rationalization ("infrastructure issue, not my fault") and routed around the constraint.

Ninety Pre-existing Failures

When I finally ran cargo clippy and cargo test myself after the second loop run,

the codebase had accumulated roughly 90 errors:

20 test compilation errors in

tokenizer.rsreferencingToken::Operator('+')— a variant that doesn’t exist. The Token enum usesToken::Plus,Token::Minus, etc. The agent had written tests against an API it imagined rather than the one that existed.4 integration test errors calling

symbolic_integration::integrate()— the function was renamed tointegrate_symbolic()in an earlier story, but the test coverage story wrote new tests using the old name.~50 clippy warnings for

assert_eq!(expr, true)instead ofassert!(expr), redundant closures,vec![]where an array literal would do, and///doc comments on statements.15 unused doc-comment warnings in property tests —

///comments onletbindings instead of//.3 runtime test failures: a tokenizer that rejected underscore-prefixed identifiers (

_x) despite tests expecting it to work, a root-finding bracket scan that missed exact zeros, and an integration test with wrong sign expectations for-x^2.

All of these were fixed in a single interactive Claude Code session. The irony: the agent that wrote the code couldn’t run the checks that would have caught these issues, but a different agent (or the same model in interactive mode) fixed them quickly once pointed at the actual error output.

Uncommitted Artifacts

After the second loop run completed all stories, the nanny detected 34/34 passing and

shut everything down. But git diff showed uncommitted changes to progress.txt —

the agent had updated the tracking file as its last act, then emitted

<promise>COMPLETE</promise>, and the loop exited before committing.

The root cause was the prompt ordering. Steps 8-10 were:

8. Commit: `feat: [ID] - [Title]`

9. Update prd.json: `passes: true`

10. Append learnings to progress.txt

Steps 9 and 10 happen after the commit. If the iteration that marks the final story done is also the one that triggers the stop condition, the tracking file updates never get committed. I fixed this with two changes:

Reordered the prompt so

prd.jsonandprogress.txtare updated before the commit, not after. All file changes happen first, then one commit captures everything.Added a safety-net commit to

loop.shthat checks for dirtyprd.jsonorprogress.txtafter each iteration and commits them if needed. Belt and suspenders.

This is the kind of bug you only find by running the loop to completion and checking the final state. It’s also a reminder that prompt ordering matters — the agent follows instructions sequentially, and if the sequence has the commit in the wrong place, the last iteration’s bookkeeping gets lost.

What I Learned

Most of the work is infrastructure

The agent wrote working Rust code from the first successful iteration. Getting the Docker container, environment variables, filesystem permissions, and process management right took more human time than any code issue. If you’re building a Ralph loop in a container, expect to spend most of your effort on plumbing.

The validation gate must be enforced, not just documented

Our first lesson was that without cargo fmt && cargo clippy && cargo test as a hard

gate, the codebase accumulates problems. Our second lesson was harder: having the gate

in the prompt isn’t enough. The second loop run proved the agent will skip the gate if the

toolchain is broken and rationalize the skip in its progress notes. The gate needs to be

mechanically enforced — either by the loop script itself or by a pre-commit hook —

not left as an instruction the agent can choose to follow.

One story per iteration is the right granularity

Multiple stories per iteration leads to tangled commits and harder debugging. One story keeps things focused and makes failures easy to trace.

Don’t use LLMs for infrastructure control flow

The nanny v1 experience was clear on this. LLMs can summarize logs and generate status reports. They shouldn’t be deciding when to restart containers or kill processes.

AI-generated tests need the same review as AI-generated code

The agent wrote hundreds of tests, and most were correct. But the linear solver tests with wrong expected values, the tokenizer tests referencing a non-existent enum variant, and the integration test with wrong sign expectations all would have been caught by running the tests. Coverage doesn’t guarantee correctness — and tests that were never actually executed provide no coverage at all.

Cross-cutting changes are a weak spot

The one-story-at-a-time approach handles isolated features well. It handles cross-cutting changes poorly. A crate rename, a function signature change, a logging convention update — anything that touches many files can regress as later stories add new code. A periodic full-project validation (not just per-story) would help.

The agent writes against its mental model, not the actual API

The most striking class of bugs from round two was the tokenizer tests. The agent wrote

Token::Operator('+') — a perfectly reasonable API for a tokenizer to have, but not the

one that existed. The actual enum had Token::Plus, Token::Minus, etc. The agent never

checked the type definition before writing tests against it. This happened repeatedly

across 20+ test assertions.

This suggests a limitation of single-shot iteration: the agent builds a plausible mental model of the codebase from the prompt and recent context, then writes code against that model. When the model diverges from reality, the errors are systematic, not random. The fix is the same as for human developers: run the code.

Prompt ordering has mechanical consequences

The uncommitted progress.txt bug was caused by the prompt listing “commit” before

“update tracking files.” The agent followed the steps in order. This isn’t a reasoning

failure — it’s the prompt author’s failure to think through the sequencing. In a loop

where each iteration is stateless, the only contract is the prompt and the files on disk.

If the prompt says to commit before updating the tracking file, the tracking file won’t be

in the commit.

Human-agent collaboration is the practical sweet spot

The first loop run (27 stories, fully autonomous) produced a working CAS but left behind compilation errors and untested code. The interactive sessions that followed (CAS-028 fixes, second loop run cleanup, infrastructure hardening) caught and fixed problems the loop couldn’t. Neither mode alone was sufficient: the loop excels at grinding through well-scoped stories, while interactive mode excels at cross-cutting fixes, debugging, and infrastructure work that requires back-and-forth judgment. The most productive workflow was using the loop for volume and interactive mode for quality.

Numbers

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| User stories (total) | 34 |

| Completed by loop run 1 | 27 (CAS-001 through CAS-027) |

| Completed by loop run 2 | 5 (CAS-029 through CAS-033) |

| Completed with human assist | 2 (CAS-025 rename, CAS-028 test fixes) |

| Library tests | 467 |

| Binary (REPL) tests | 31 |

| Integration tests | 31 |

| Property tests | 14 |

| Doc-tests | 15 |

| Total tests passing | 558 |

| Clippy warnings | 0 |

| API cost (loop runs) | ~$30 |

| Human time on infrastructure | ~4 hours |

| Human time on code fixes | ~2 hours (CAS-028, round 2 cleanup) |

Running Your Own

The infrastructure is in the repo. To run a similar loop:

- Write a

prd.jsonwith user stories and acceptance criteria. - Write a

prompt.mdwith iteration instructions and a validation gate. - Build the Docker image:

./scripts/docker-build.sh - Set your API key in

.env - Launch:

./scripts/docker-run.sh - Optionally, run the nanny:

./scripts/nanny.sh

The pieces that matter most:

- Clear acceptance criteria. Vague stories produce vague implementations. Specific criteria give the agent something concrete to verify.

- A validation gate the agent can’t skip. Document it in the prompt, but also consider

enforcing it mechanically in

loop.shor via a pre-commit hook. If the toolchain is broken, the agent will skip the gate and rationalize it. - Prompt ordering that commits last. Update all tracking files (PRD, progress log)

before the commit step, not after. Otherwise the final iteration’s bookkeeping gets

left uncommitted. A safety-net commit in

loop.shcatches any stragglers. - Preflight checks. Verify the API key, network, C compiler, and toolchain work before burning iterations. Silent failures waste time and credits.

- Isolation. Docker sandboxing lets you run

--dangerously-skip-permissionswithout worrying about what the agent might do to the host. - Budget awareness. Set usage limits or monitoring on your LLM API costs. 30 stories cost us ~$30; a runaway loop with failing iterations will burn credits on retries.

Prior Art and References

- Geoffrey Huntley’s original Ralph Wiggum post — the origin of the technique

- A Brief History of Ralph — timeline of adoption and community development

- CodeBun’s Medium article — the specific implementation we based our PRD format, prompt, and loop.sh on

- snarktank/ralph — community reference implementation